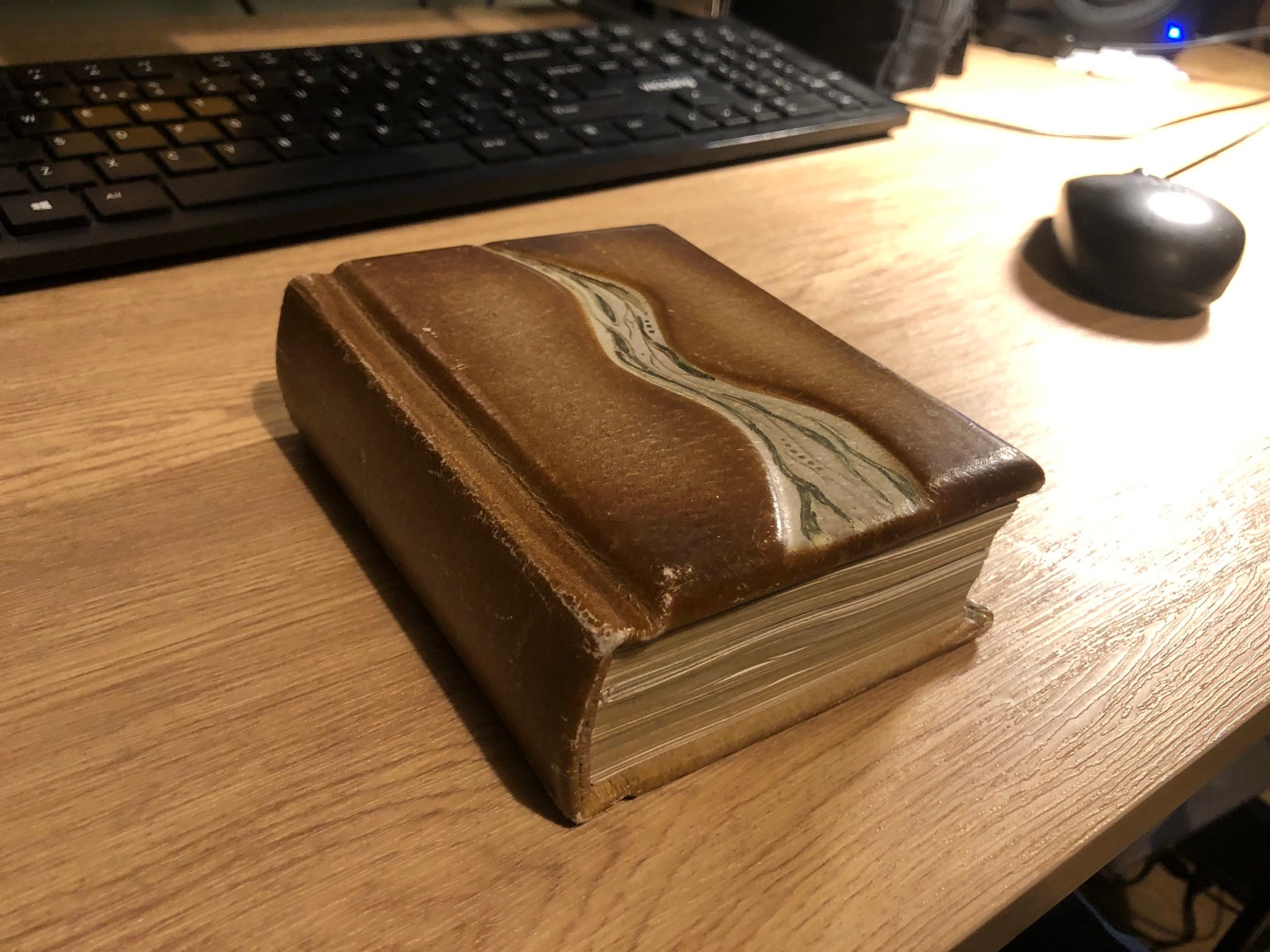

If you’re looking for a way of bringing about some change in your work life balance, the book Time Off by John Fitch and Max Frenzel might be a good place to go for some inspiration.

Fitch and Frenzel first provide a potted history as to why we hold the view of work we currently do, how our slavish attention to time and whether we are using it productively results in unnecessary and unhelpful worries. Guilt about how we spend our time invariably results in us spending more not less time working – a way of compensating for the perceived lack of productive use of our time.

This view of time as being valuable, a sacred commodity which needs to be appropriately used, is something the 18th-century upper classes were keen on cultivating in order to control the lower classes. Protestant religion adopted a ‘work ethic’ for this very reason, hence the status found in working hard.

Productivity acquired a sought-after status. Busyness – ‘productivity without output’ – quickly became a go-to activity, the stress resulting from which a kind of proof for receiving our reward or pay as a result. This unproductive productivity then led counter-intuitively to poor performance, exhaustion and ultimately burnout.

For Fitch and Frenzel, we might benefit from returning to an earlier view of time, as exemplified in two Greek Gods Chronos, measured time or a quantity of time, and Kairos, unmeasured time or the quality of time spent. We learn as adults to ‘keep track’ of Chronos time and often berate ourselves when we run out of it or fail to manage it well, but rarely embrace the opportunities Kairos, unmeasured time (or just being in the moment) as we did as kids.

How might our view on our own productivity and what productivity really means if we released our grip a little on Chronos time?

According to Josep F. Mària, Associate professor, Department of Social Sciences at Esad Business School, Barcelona, “A kairos moment can open up anywhere… It can be as minute as recognising that sudden need to take a walk in the fresh air to clear your head, trusting that such a simple act of self-care is not a waste of time, but time you can afford.”

In ‘Time Off’ Fritch and Frenzel suggest focussing less on time passing and concentrating more on ‘the desity’ of every single moment.

Whilst this may not immediately seem possible in a work scenario where we’re negotiating our schedule in amongst everyone else’s timescales, I like the idea of shifting focus even for only very short spaces of time in order to maximise the chances of getting into a flow state.

The first few chapters of Time Off also helps me to prepare well for scheduled time off too, granting permission for that rest at the same time as reinforcing the need for it. Given that rest is necessary for the body to repair and restore, why we wouldn’t we give ourselves the best chance to achieve that?