It’s twenty years and a day or two since I boarded an early morning flight from Heathrow to Latvia to attend the Eurovision for the first time.

I’d blagged my press accreditation for behind-the-scenes access by ringing the BBC switchboard and asking to be put through the producer responsible for the UK’s entry that year. ‘You’re just in time,’ said Dominic the Producer, ‘get your application in by 4pm and I’ll approve it.’ I finished the call, stamped out my Marlboro Light, and headed back to the day job.

By the time I got home from work that evening, the application had been approved. The flights were booked the following day. I flew out to Riga a month later. It was the furthest distance east I’d ever gone. I still couldn’t quite believe my front and securing what I’d secured. The prospect was epic.

“Be in the moment,” advised my therapist Anne Cole. Sage advice. I was a torment of dissatisfaction, bewilderment and curiosity. What was emerging in our weekly Gestalt-infused sessions was a desire to write – scripts, books, whatever – I just wanted to write. I needed a story. There needed to be something to discover. Me catapulted into my dream world – Eurovision – seemed like an obvious one.

There were other reasons for forking out two grand on flights and my kind of accommodation for a week. I wanted to make contacts, discover an alternative career, dare to be someone different. Just how far could pretending to be the person I wanted to be actually take me? What would I learn about the thing I loved since childhood that would help me in the next stage of my career (whatever that was)? What would I learn about myself?

I can still recall the detail – the feel of the press centre floor under my feet, the shoes I was wearing, the sight of the thousand press passes waiting to be collected at the accreditation centre, the smell of coffee and freshly lit rolling tobacco. The unfamiliar feeling of achievement. Chance conversations with influential people, cheap beer and the sense of incredulity that there might be others who loved Ding Dinge Dong with the same uncontrollable enthusiasm I did all contribute to the high I still recall twenty years on.

It was by no means a breeze. I felt quite stupid, out of the loop, and unconvinced my editorial angle – the real people behind the performers and songwriters – had the necessary gravitas. I was lonely. I’d forked out stupid amounts of money to actively make myself look like an idiot. I was the biggest fraud amongst a sea of tight white t-shirts and sneering eye-rolls.

Nor was I convinced I’d read the press room well. Didn’t appreciate quite how important the playing the game was. Hence why, when faux lesbian duo Tatu sought to preempt the now familiar populist playbook by failing to turn up to rehearsals followed by a surly disinterested presence at their press conference, I responded to an invitation from the facilitator for questions from the international journalists I stepped up to the microphone and spoke direct from the heart: “It’s great to see you both here for the press conference even if you are busy doodling, but do either of you have a sense whether we can rely on you to turn up for the final on Saturday night?”

My heart pounded amid the unexpected and bewildering press conference applause. I was a jibbering wreck. Minutes later I sat at a desk crying on the phone. Yes. Crying. People were supportive if a little confused. Perhaps they looked on with a sense of pity. Poor little fanboy. Bless him for getting carried away like that.

It’s taken me 20 years to understand my reaction. And it’s worthy of inclusion here.

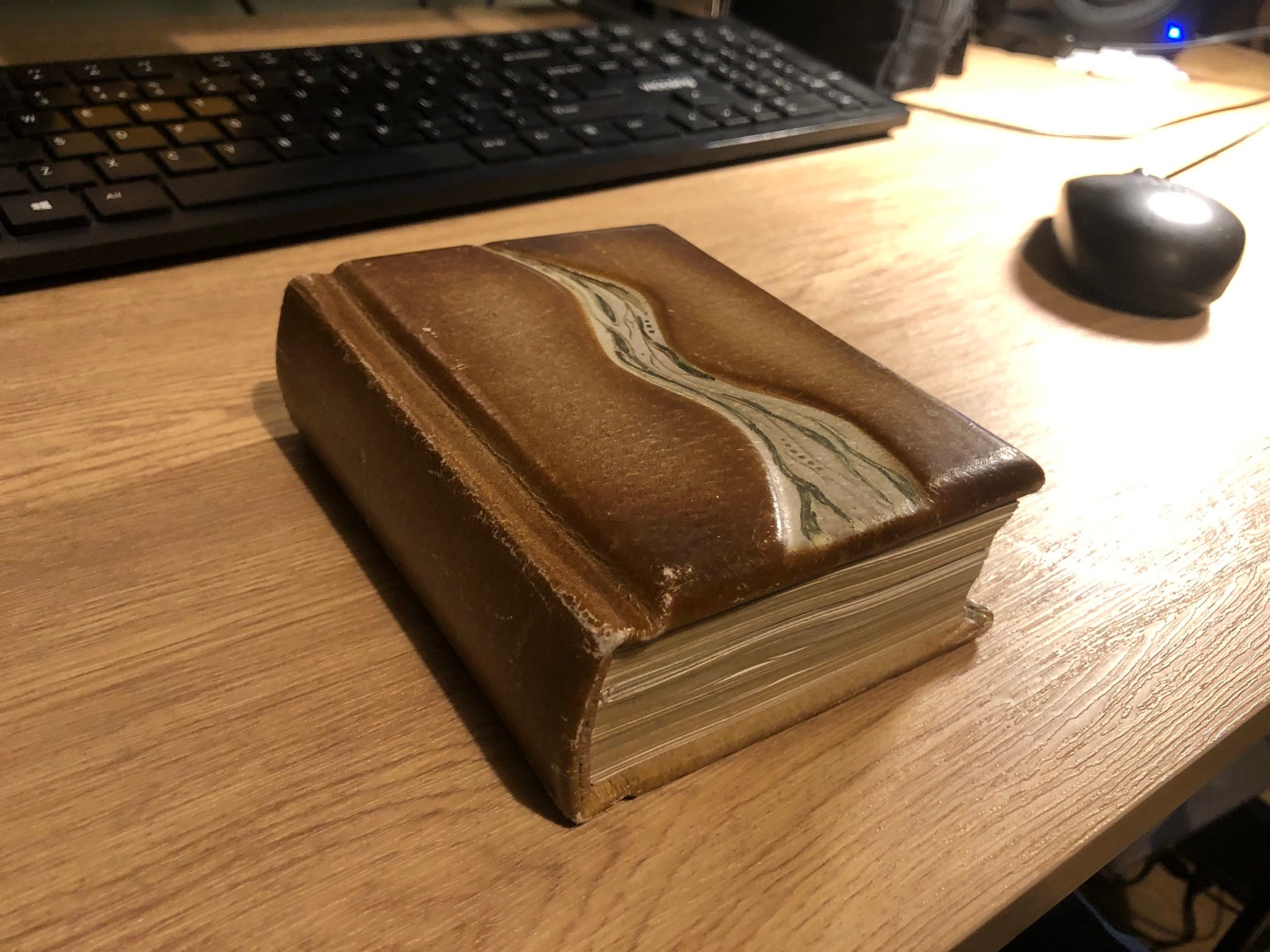

Hours after the Eurovision winner had been announced and all in the U.K. began reflecting on what continental humiliation felt like, I packed up my bags, checked out of my hotel, and browsed a nearby gift shop. Pride of place in the centre of the window was a small book with a hard cover. This chunky handheld affair contained a hundred pages of cartridge paper, neatly bound with stitching. “I’ll get that for Mum and give it to her for Christmas.” There was a sense that if the only copy I could write for this eye-wateringly profligate trip was nauseatingly self-indulgent I could at least put a brave front on it all and legitimise things with a well-meaning gift for my mother.

Two years later I receive the book back on my birthday populated with pencil drawings of various locations my mum presumed to be important to document. Among the inevitable pictures of the house where I grew up, there were pictures of the local steam engine rally, my school, Snape Maltings, Southwold, the flat I moved into in Clapham with my now husband, the same person who dropped me off at Heathrow, and the house we live in together now.

Eighteen years on the hairspray she used to fix the drawings on the page is still redolent, even if my mum is increasingly distant and detached in a nursing home.

And today that same book has taken on a new function.

Since my mother’s stroke back in August 2021, all manner of layers have been peeled away exposing something unsettling. What has for my entire life been described as my consistently and reliably intense impatience with myself now came into an entirely different focus: what often presented itself as a tense kind of irritation on the surface was in fact evidence of deep-seated frustration and powerlessness.

Odd to discover given that I don’t recall ever being frightened of speaking up in the face of perceived injustice or unfairness in the past. Only that I was terrified when I did so when the other party responded even more enraged.

Only now when I recall those moments when I did speak up I remember how it was always met by uncontrollable or disproportionate rage. Think of the blowback after a nuclear bomb and you’ll get a sense of what I’m talking about. That’s how it felt. Two teachers in particular spring to mind – let’s just call them arseholes because that’s what they were. Their disproportionate and inappropriate behaviour cast the mold. I learned early on that speaking up or challenging was wrong. It was impertinent. Because I was wrong. Because I was here by grace and favour and chance. If I dared step out of line I deserved everything I received as a result.

When I recall that press conference in Riga and the tears that followed I remember relief, not fear. Certainly not shame. Surprise perhaps. Accomplishment maybe? I’d suddenly discovered my values even if I didn’t realise what values were or why they were important. I’d put myself out there. I’d stepped into the arena, just like Brene Brown talks about.

If you’re not in the arena getting your ass kicked, I’m not interested in your feedback.

Brene Brown, Call to Courage, Netflix

These experiences had – truth be told – started at home. But now in 2021, grappling with the loss of a parent (grieving a parent who is still alive is a weird experience), I was becoming accustomed to how thirty years of repressed anger was now something that could unhelpfully spurt forth like a volcano. The torment of conflicting emotions that resulted, even being more aware of the physical experience of frustration was … unnerving.

Amidst all of this weirdness and overwhelm, there on the bookshelf the notebook from Riga presented itself like a secluded harbour in a torrential storm. The book of pencil drawings my mother gave me in 2005. Something to cling onto.

Here in my hand, fond memories of a miraculous trip layered with creative endeavour gifted from one generation to another and back – inadvertently acting as an NLP anchor for acceptance and ultimately forgiveness. This strange notebook had the effect of making it possible to accept what happened in the past, making it more possible to let go of it.

Make peace with what’s underneath and everything else will follow suit, neatly, calmly, and resolutely. Acceptance it seems is stumbling on an unexpectedly calm air-conditioned room with free drinks and a taxi on-account to take you home. Forgiveness? Well that’s a different room possibly on the next floor but absolutely within reach.

And this is important because by accepting and forgiving we can rid the irritation and impatience and the self-flagellation that sometimes crops up unhelpful in day-to-day interactions.

This state isn’t an end point but a work in progress. Both states are an ongoing commitment to catching unhelpful learned behaviours, and self-limiting and core beliefs that make managing conflict unnecessarily difficult. Without looking at these things with some healthy heartfelt curiosity we’re ill-equipped to establish our own boundaries. If we’ve not been able to set our own boundaries how can we possibly be able to help others set theirs? Managing conflict depends to a large extent on being able to estbalish our own boundaries first. Sometimes the first step is managing ourselves so that we feel more able to show up in the arena to get our ass kicked.

There’s another thing that screams out (not so much angrily but passionately) and that’s the difference in expectations I had twenty years ago when I went to Latvia compared to now.

I didn’t embark on the trip because I thought there was a guarantee I’d get a job in journalism off the back of it. I went there in search of a possibility and discovery. It was the most expensive of self-funded self-indulgent networking opportunities that in some way I felt embarrassed having to justify to anyone. And yet at the same time, it was incredible. Nothing that followed matched it, except maybe Austria hosting and working with the brilliant Malcolm Prince at Radio 2 (that was very special) or meeting the British ambassador in Ukraine.*

So many people today who are around about the age I was when I went to Riga seem to expect a guaranteed return for anything. We have somehow led a generation up the garden path with all manner of unrealistic promises, suppressing them of curiosity and starving them of serendipity in the process. Discovery and curiosity was the goal for me in Riga, 2003. Part of the agreement I made with myself to go to Riga was to accept the risk it wouldn’t work. Being prepared to fail is vital. That’s how we learn.

What I got, as a result, took a long time to come good. Its as though the wine has been in the cellar for twenty years and its only now there’s been a reason to open it. And taking a sip, it tastes good.

All this from a flight of fancy, brokered during a cigarette break in April 2003, booked on a credit card, and legitimised with a notebook.

Jon Jacob works with executives and leaders in organisations across the world. If you’d like to work with him email jon.jacob@thoroughlygood.me. For more information on his work see the Thoroughly Good Coaching homepage.

* Additional epic moment since remembered: visiting the EBU to see former BBC colleagues and sneaking a chance to lift the Eurovision trophy. See below.